New Orleans is a food city, but it’s also a city with its share of touristy food gimmickry if you don’t know where to look. Melissa Martin’s Mosquito Supper Club in the Garden District, which serves up food from her bayou upbringing, is very much the real deal. (Several of our New Orleans Black Book contributors rave about it here.) When, a couple of years ago, we excerpted a few paragraphs and recipes from Melissa’s first cookbook in WM Brown, I was hooked by the stories the James Beard winner conjured of her food roots:

The Cajun food I ate growing up wasn’t loud or flashy—no bam!—and it was not consumed with copious amounts of beer or alcohol. We ate simple, whole foods, and we ate with the seasons. We ate a cuisine rooted in the hard work of fishermen and the palates and grace of mothers and wives commanding their stoves. I opened Mosquito Supper Club restaurant in New Orleans because I wanted people to learn about the real Cajun food I grew up with—developed by descendants of French colonists who were exiled to Louisiana in the 18th century, but also influenced by Native American, African and Spanish cuisines and techniques. I wanted to cook with Louisiana seafood and local produce; I wanted to forage for blackberries when they were in season and process okra when it was abundant and serve them both in ways that feel familiar to me. I wanted to bring the best of the bayou to the table and shine a light on what was happening to the place where I grew up and the people who live there.

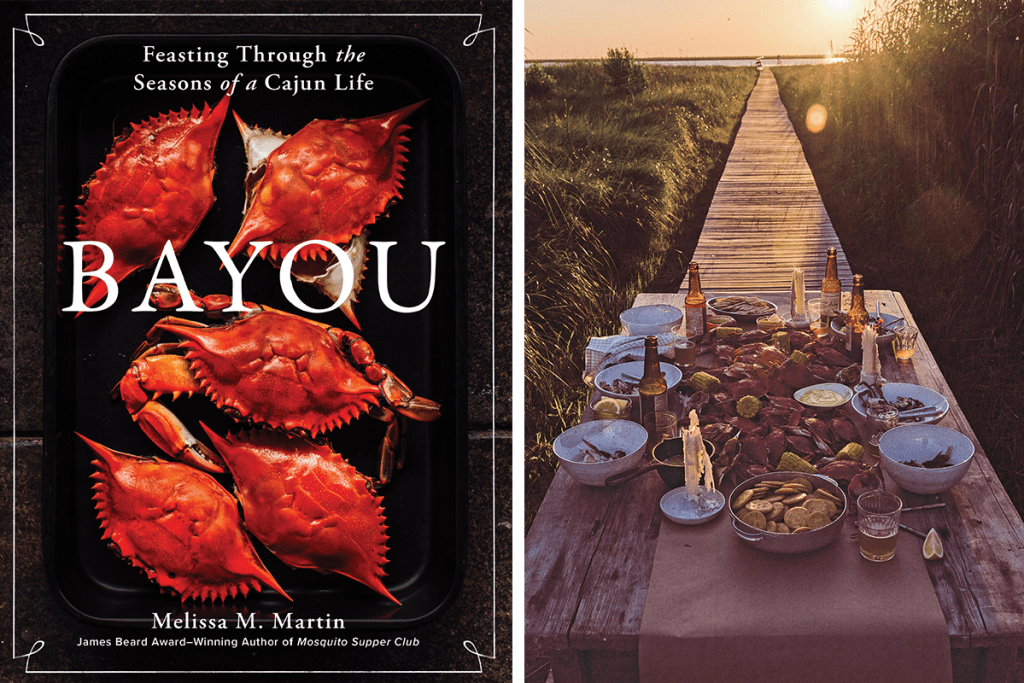

So, when her second book—Bayou: Feasting Through the Seasons of a Cajun Life—came out late last year, I was so happy to discover that she leaned in even deeper to those roots, conjuring a sense of place and community and the rhythms of the fishing village in Terrebonne Parish where she was raised and her parents still live. And, of course, I wondered: how do you visit this region?! Recently I had the chance to chat with Melissa and ask where a traveler might find the honest cooking of her childhood, and how to make a long weekend of eating and exploring across the bayou. We also reprinted her recipe for a Crab Boil in case you want to bring a little bit of the Bayou home.

You grew up in a bayou community on the South Louisiana Coast. Can you give us some idea of its character and how far back your family goes there?

Chauvin, the town where I grew up in Terrebonne Parish, was settled by fur trappers who came down to the bayou, either from Nova Scotia or directly from France. Chauvin, like New Orleans, is about 300 years old. Cajuns who lived in Acadia throughout the Canadian Eastern Seaboard were expelled by the British Crown, and were sent walking or put on boats and taken away. Some wound up in South Louisiana and began settling and encouraging other folks to join. (This is the story in Longfellow’s famous poem, “Evangeline.”) Meanwhile, other boats were coming directly from France to New Orleans, and those families were sent to live in the countryside. We can trace our roots back to Southwest France and Corsica. My extended family were in the seafood business and also trapped fur. My mom and dad have lived in the same house on the bayou where I grew up for 56 years.

Farther south at the end of the road is Cocodrie, which is still a working fishing village. I was just there last weekend doing a food event, and it remains an Eden of resources. I fall in love with Cocodrie over and over every time I go down the bayou—absolutely the most beautiful sunrises and sunsets I’ve seen in my life. Last weekend, I was sitting on the screen porch watching the sun come up, watching shrimp boats skimming on the bayou, watching people fish and the fish jump out the water, the pelicans and all these birds—it’s just absolutely gorgeous.

And how far is all this from New Orleans?

Leaving the city, you start traveling southwest for almost a full hour, parallel to the Gulf of Mexico, then when you get to Houma, Louisiana, you drop south. To get to Chauvin, you travel south another half hour, and if you keep going further you will be at the end of the road, Cocodrie, and the barrier waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Sometimes you get a little disoriented. You’re always near water, you just can’t see it sometimes because of the trees.

I’m from Bayou Petit Caillou, and there are all these fingers with little communities on each side of the bayou that make up Terrebonne Parish—Montegut, Chauvin, Dulac… it goes on. And then the same thing for Lafourche Parish, which is next to us. Chauvin is a town of about 1,000 people. There used to be more, but we’re losing people all the time, especially after they decommissioned all the public schools after Hurricane Ida. But it’s still a very tightly knit, sustainable fishing village.

Who were your food influences growing up and how have you built on them?

My mom, grandmother, and aunts. But I didn’t necessarily learn to cook from them. I just ate their food. My grandmother lived next door, and I had four aunts that lived next door to us, too. So I developed an appreciation for the flavors and what the building blocks were.

When I started learning how to cook it on my own, I cooked on the phone with everybody, and I knew how it needed to taste. And then I worked for some great chefs around the country, so I was able to hone my restaurant skills and know how to then take something and scale it for restaurant production. At home, everything was one-pot meals. The funny thing is, if you come into Mosquito Supper Club we give you so much food, whereas at home the meal would have been the soup, or the meal would have been the gumbo. On Sunday we’ll have gumbo, potato salad and rice, and that’s our meal. Whereas I give you a whole cornucopia of food on the table.

How would you define the food of The Bayou? What are some of the basic elements of Cajun cuisine that would be helpful for a traveler to understand?

All these small bayou towns are known for their incredible abundance of seafood, which is the basis of most of the food I serve at Mosquito and write about in my books. In my first book, I was very adamant to talk about the seafood that we use in the industry, what it means to be a fisherman, what it means when you don’t buy domestic seafood, what shrimpers get paid, the brass tacks of working in the fishing villages. And how we ate growing up, which was that you ate from the water, as my parents still do. My second book, Bayou, also has a lot of seafood recipes, but I also put in some other things we ate, like rabbits and ducks and chicken and salt pork and sausage. Not a lot of beef—Cajuns raise cattle, but they raise cows for milk, not to eat beef. If it’s shrimp season in the spring or fall, you’re eating a lot of shrimp and crab. When you get to crawfish season in spring, you’re eating a lot of crawfish. And then March is the best time to eat at my restaurant, because you can have fish, finfish, crawfish, crab, shrimp, oysters… the whole cornucopia. But, I mean, my parents have never purchased seafood. They only ever got it from the source, from my cousins, or they go and fish it themselves. But that’s what we still eat, the main ingredients that we cook from.

Who else (besides Mosquito Supper Club, of course!) would you say is doing great food reflective of the region? Where do you send your friends?

It’s hard to get really good Cajun and Creole food, because the best is in people’s homes, you know? There are no restaurants in Chauvin. You can get a good gumbo from the Link restaurants, though—Herbsaint, Pêche or La Boulangerie. There’s a restaurant in Bayou Grand Caillou called Ceana’s, where you can get a good fried po’ boy.

In Western Louisiana, there are a ton of places for boiled crawfish during crawfish season, like Cajun Claws, Wilson’s and Hawks. If you just want to eat boiled seafood, there are places that are really good. But sometimes at places that have really delicious boiled seafood, if you order a crab cake, it’s not good at all, because they get their crab cakes from Cisco, you know? You really have to know what to order. [see Melissa’s recipe for a Crab Boil below!]

It’s just really hard to come by food that is connected to the culture, because it’s just in people’s houses. That’s why I started the restaurant, to try to take it out the house and bring it to the table and keep it the way we had it growing up. To make traditional Cajun food that is typically served behind doors in home kitchens.

Can you recommend a couple of great long weekend trips in the Bayou region? Say, tack-on trips from New Orleans that would offer a great taste of local culture.

For an easy getaway from New Orleans, you could drive down to Chauvin and see the sculpture garden and the bayou, stop at Marty J’s for a shrimp po’ boy, have a coffee at Cecile’s in Cocodrie, hire a charter fisherman to take you on a bayou tour—you really have to get out on the water to experience it; they say the bayou is one of the longest main streets in the world—and then rent a camp for a peaceful weekend of watching the sun rise and set. (You can find camps on VRBO or Airbnb.)

In Lafitte, which is around 45 minutes from New Orleans, you can get some boiled seafood at Higgins, where I get my crab, and go on a swamp walk—there’s a heron rookery there and it’s really beautiful. So that’s a good way to see another fishing village, but also get some food directly from people you know. There are other fun things there, like a Cajun Museum and a Jean Lafitte puppet show with all these animatronics puppets—it’s pretty funny.

If you’re up for going a little bit further, In Lafayette you could stay at Maison Madeline and go on a swamp paddle in Lake Martin. It’s peaceful and dreamy. Stop at Wild Child Wines for a great snack homemade bread, cheese, charcuterie and sandwiches, sometimes pizza too, and wander through this part of Western Louisiana. Visit Nancy at the Kitchen Shop, get a fried crawfish po’boy at Bon Creole in New Iberia, stay at Moon Over Bayou Cottage in Franklin. You could also go to Avery Island and take the Tabasco tour. I don’t even use Tabasco, but it’s still fun to go over there, and everything’s so close to each other. There’s lots of good music, good dancing, and good food around there. You really could make a weekend in Lafayette, especially if it’s one of the festivals they have there, like the Black Pot Festival or Festivals Acadians.

Speaking of festivals, in your book, you define the regional food not through seasons but through events/celebrations. What are a few signature events that are fun for visitors to try and catch?

Yes, in the new book I wanted readers to feel the mood of each season, since it is informed by the food that is available or not available at that time. It seems like there are multiple festivals and events every weekend. You can follow Louisiana Tourism and pick your favorite, whether it’s a boucherie by Las Pache, or a beignet festival in New Orleans. Let your palate be your guide. We have the Rougarou Festival in Terrebonne Parish, in October, which is super fun, and you can try a whole bunch of local foods. My good friend growing up, Jonathan Foret, puts it on, and he’s adamant about the food and the ingredients being correct. They peel their own shrimp, they pick their own crabs, they forage their own blackberries for the festival. It’s kind of modeled after this festival we had growing up called Lagniappe on the Bayou, which doesn’t exist anymore. And if you’re in Houma, which is the town near Chauvin, we have a dance hall where they play Cajun music, and they will have a big pot of jambalaya—you go get yourself a bowl and pay five bucks or whatever. So there are still remnants of how things were.

You Louisianans are all so celebratory!

We are! But I mean, I run a restaurant, so I feel like I throw a party every day.

What are some great food gifts/bring backs from Southern Louisiana?

I always say to bring back filé. It’s sassafras leaves that have been pounded and used to make filé gumbo. At the restaurant, we make filé ice cream—it reminds me of a matcha, with a minty, herbaceous smell. Filé was indigenous, the way American Indians would thicken soups and way before okra or roux. You get roux from your mother sauce in France, you get okra from Africa, and you get filé from the native country. You can get it at Clements In Chauvin; it’s made by an indigenous woman who makes it the old way, and she sells it there.

And then people are always asking for Cajun seasoning, but we make fun of Cajun seasoning, like, what is it? My mom’s food wasn’t spicy. It’s basically salt, black pepper and cayenne, and after that it could include bay leaves, thyme, dehydrated garlic, onions, bell pepper or celery. There’s always Louisiana hot sauce, but you can get that anywhere now.

RECIPE: Crab Boil with Potatoes and Corn

SERVES 8

Boiled crabs create a slow eating experience where the food demands work; no one can fly through the peeling of crabs, which requires patience but is well worth the effort. You’ll want to round out the meal with potatoes, corn, lemon aioli, and bay-scented drawn butter.

10 pounds (4.5 kg) yellow onions, peeled and halved

3 bunches celery (about24 stalks), cut into 4-inch (10 cm) pieces

24 lemons (about 6 pounds/2.7 kg), cut in half

24 bay leaves

½ cup (45 g) cayenne pepper

½ cup (70 g) whole black peppercorns

½ cup (55 g) mustard seeds

½ cup (43 g) coriander seeds

48 live medium-to-large blue crabs

2 cups (280 g) kosher salt, plus more as needed

24 red potatoes

8 to 12 ears corn, shucked and broken in half

(Lemon Aioli and Drawn Butter with Lemon and Bay for serving)

Place a strainer insert in a 10-gallon (38 L) stockpot and fill halfway with water. Add the onions, celery, lemons, bay leaves, cayenne, peppercorns, mustard seeds, and coriander seeds. Bring the water toa boil over high heat, then reduce the heat to low and simmer until the vegetables are soft and the stock has developed a delicious vegetal, lemon-scented, spicy aroma, about 1½ hours.

Raise the heat to medium-high and return the stock to a rolling boil. While it’s heating, rinse off the crabs with cold water from a hose. You can do this in a large strainer; we use what’s called a bushel, which holds a lot of crabs or shrimp at one time.

Add the crabs to the stock and use tongs to immediately press all the crabs under the liquid. Cover the pot and let the stock come back to a rolling boil. Once it does, cook the crabs for 15 minutes.

Turn off the heat, add the salt to the pot, and let the crabs soak for 15to 30 minutes. Taste a crab by peeling one and trying the meat; if you think it needs more seasoning, add more salt and spices. Remove the strainer insert and let the crabs drain, then place them on trays for eating or on a table covered with newspaper.

Replace the strainer in the pot and bring the stock back to a boil. Add the potatoes and boil until they can be pierced with a fork, about10 minutes, then strain and place them on the table. Replace the strainer once again and boil the corn for 5 minutes. Strain and set on the table alongside the crabs. Serve with the aioli, drawn butter, and crackers.

Excerpted from Bayou by Melissa M. Martin (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2024. Photographs by Denny Culbert.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.